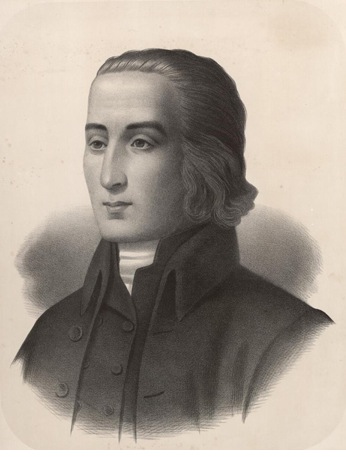

William Williams of Pantycelyn

HYMN WRITING

In the seventeenth century actual church worship in all the different tendencies and throughout the British Isles was still based on the psalms and other passages taken from scripture, albeit, in the Calvinist tradition, put into simple verse forms suitable for singing. Calvin had high quality verse from Clement Marot and Théodore de Bèze, the Welsh had high quality verse from Edmwnd Prys, the Scottish and English versions were somewhat less impressive but still serviceable. It was only in the eighteenth century that newly composed hymns began to be important, starting with the work of the English Congregationalist, Isaac Watts. But the great flowering of hymn-writing came in the context of the Methodist movement both in England with the hymns of Charles Wesley and in Wales, with the hymns of William Williams of Pantycelyn (the name of a farmhouse near Llandovery). (22)

(22) Mention of Charles Welsey provided an occasion to hear the lovely version of his hymn Jesus lover of my soul as played by Maddy Prior and the Carnival Band.

In addition to his hymns Williams wrote two epic length poems in Welsh - A Prospect of the Kingdom of Christ, which was an ambitious account of the divine plan for the creation and salvation of humankind, and Theomemphus, an account of the travails of an individual soul. A 'selective translation' of Theomemphus has been published. (23) According to the account by Herbert Hodges (24):

'The poem was conceived and executed in conscious rivalry with Bunyan. Unlike The Pilgrim’s Progress, which picks up its hero’s story only at the moment of his conversion, Theomemphus traces its hero’s spiritual history from the cradle to the grave; and whereas Bunyan’s pilgrim is separated from his family and neighbours, a solitary traveller whose only friends or enemies are those whom he meets on his way, Theomemphus is shown experiencing the vicissitudes of sin and grace in the bosom of a Christian community, undergoing its discipline, rising to a position of influence within it, having an unhappy love affair and later on an unhappy marriage, but always as a real man and living in real circumstances. Pantycelyn says he has tried to make him a typical representative of the New Testament Christian, in the light of Scripture but also of contemporary experience. And whereas, in The Pilgrim’s Progress, Christian’s spiritual conflicts are all shown as conflicts with external enemies, Pantycelyn lets us follow the internal conflicts in Theomemphus’ soul. In a word, his account of the spiritual life is fuller, more realistic and more intimate than Bunyan’s.'

(23) Pursued by God - A Selective Translation with Notes of the Welsh Religious Classic "Theomemphus", Bridgend, Evangelical Press of Wales, 1996

(24) H.A.Hodges: 'Over the distant hills - thoughts on Williams Pantycelyn', first published in Brycheiniog no 17, 1976-7. Republished in E.Wyn James (ed): Flame in the mountains - Williams Pantycelyn, Ann Griffiths and the Welsh Hymn, Essays and translations by H.A.Hodges, Talybont, Ceredigion, Y Lolfa Cyf, 2017. I have it in a Kindle edition that doesn't give page references.

In a different essay, (25) also republished in Flame in the Mountains, Hodges gives a summary account of The Prospect: (26)

'In it the Father explains his plans to the Son before the creation of the world. He is going to create a world in which there will be human beings, and they shall be "capable of falling, or of standing and living", and he will ‘suffer them to fall’. But he does this in order that grace may abound. The Son is to take flesh and suffer and die, and so win salvation for all who shall believe in him. A Covenant on these terms is made between the Persons in eternity. God’s successive covenants with men are merely the working out of this, they are part of the provisions of this prior Covenant in heaven. There is a hymn which states the doctrine clearly and well ... "Before the world was formed, before the bright heavens were spread out, before sun or moon or stars above were set in place, a way was planned in the council of Three in One to save wretched, lost, guilty man. Grace was treasured up, an endless store, in Jesus Christ before a law was given to the sea; and the blessings of the precious design ran like a strong river flooding through the world."'

(25) 'Flame in the Mountains. Aspects of Welsh Free Church Hymnody' Religious Studies No 3, 1967-8, Cambridge University Press.

(26) An English translation by Robert Jones was published in 1878 as A View of the Kingdom of Christ, (London: William Clowes and Sons).

This is, in perhaps a rather benign form, the extreme Calvinist 'supralapsarian' position, that the whole scheme of the Fall and Salvation had been decided in a covenant made between the Father and the Son before the beginning of time. (27) Not having read it myself I can't tell if Williams draws out the implications of what is called 'double predestination', that if some have been chosen before the beginning of time to be saved, then others have been similarly chosen to be eternally damned. It is this implication that the Wesleys tried to escape through their adoption of an 'Arminian' theory of grace. Although these issues were very hotly debated, with most of Wales firmly on the 'Calvinist' side, I would nonetheless regard Wesleyan Arminianism as part of the general argument for a widening of the original impetus given by Calvin in Geneva. It is true that the Wesleys - and George Whitefield who defended the Calvinist doctrines of predestination, irresistible grace and the perseverance of the Saints - started out in the High Church Anglican tradition. But the natural development of the revival movement led them to abandon everything that was distinctive in that tradition - a methodical system of ascetic practices, an emphasis on correct liturgical procedure - and to adopt what had become characteristic of Calvinist nonconformity - gatherings of Christians who believed themselves to be saved, meeting separately from their more lukewarm fellow church goers and, in those gatherings, a very plain order of preaching, singing and extempore prayer.

(27) The more common position is the - to my mind quite illogical - 'Infralapsarian' position that the scheme of salvation was decided after, and as a result of, the Fall. As a Supralapsarian quite reasonably asked: 'Does this mean God was taken by surprise by what Adam did?' It opens the way for the even more absurd 'Christian Zionist' position that God was taken by surprise when the Jews refused to accept Jesus as the Messiah and the Christian church had to be cobbled together as a stopgap until Jesus could come back and give the Jews a second chance to get it right.

But to return to William Williams. Hodges gives some very beautiful translations, largely love songs addressed to Jesus often using images from the Song of Songs (also used extensively by Isaac Watts (28)):

'If here the beauty of thy face makes myriads love thee now, what will thy fair beauty do yonder in eternity? Heaven of heavens will wonder at thee ceaselessly for ever. What height will my love reach, what marvelling then, when I shall see thy full perfect glory on Mount Zion? Infinity of the whole range of beauties in one. What thoughts above understanding shall I have within me as I consider that the perfect pure Godhead and I are one? Here is a bond which there is no language to express. A bond that was made in eternity, sure, strong, very powerful; a myriad years cannot break it or undo it at all: it abides and will abide while God remains in being ...' (Aspects of Welsh Free Church Hymnody)

(28) And by Ann Griffiths. I haven't discussed Ann Griffiths here because, although some versions of her hymns were known and popular in the nineteenth century, it wasn't until early in the twentieth century that the original transcriptions of her poetry and therefore the full extent of her genius became more generally known.

'The earth with all its charm wholly vanishes now, and the host of its strong temptations falls to the ground; all the world’s flowers have lost their colour; nothing is pleasant but my God. The sun and stars in the sky all pass away from before me; thick black darkness comes over every bright and pleasant thing: my God himself is beautiful, is great, and all in all in heaven and earth. ...' (29)

(29) 'Williams Pantycelyn, Father of the Modern Welsh Hymn', A paper read at the Hymn Society of Great Britain and Ireland's Annual Conference in Cardiff, July 1975, and subsequently published in the Society's Bulletin, no 135, vol 8:9 (February 1976) and no 136, vol 8:10 (June 1976). Republished in James (ed) Flame in the Mountains.

and

'There let my food and drink be under the fine branches of the tree whose root is on the earth and its branches in bright heaven; a man in whom the Godhead dwells, fruit growing upon him in abundance; under him is shade for the faithful from morning until evening.' (Over the distant hills)

And here is an English translation of one of his best loved hymns (30):

Speak, I pray Thee, gentle Jesus!

O, how passing sweet Thy words,

Breathing o’er my troubled spirit

Peace which never earth affords.

All the world’s distracting voices,

All th’enticing tones of ill,

At Thy accents mild, melodious,

Are subdued, and all is still.

Tell me Thou art mine, O Saviour,

Grant me an assurance clear;

Banish all my dark misgivings,

Still my doubting, calm my fear.

O, my soul within me yearneth

Now to hear Thy voice divine;

So shall grief be gone for ever,

And despair no more be mine.

(30) I played this as sung by the LLanelli Free Evangelical Church.