A MUSICAL PROLOGUE

I began this talk by playing Dark was the night, cold was the ground (in which our Lord was laid) by the Gospel singer and guitarist, Blind Willie Johnson. It can be found easily on Youtube. It is a meditation of the death of Jesus. Although Johnson sings it wordlessly it would be sung in church as 'a slow, solemn responsive psalm, in which the preacher intoned the first phrase, very slowly, and the congregation responded with the same measured solemnity.'(1)

(1) Samuel Charters: Introduction to The Complete Blind Willie Johnson, Columbia (Sony) Records, 1993. 'Dark was the night' was recorded in December, 1927.

Johnson sang - or at least recorded - only Gospel music. He was based in the town of Marlin, Texas, singing on a different street corner to the blues musician Blind Lemon Jefferson. Unquestionably he believed himself to be a member of the Christian Church. But he wasn't a member of the Catholic Church, or of the Orthodox Church. The churches he did attend did not regard themselves as institutionally THE Christian church. He would have felt free to attend different church institutions. He would have recognised them as true churches not because of any constitutional continuity but because they preached the Gospel and administered the sacraments. Two sacraments - baptism and 'the Lord's supper'.

There would be no fixed liturgy. The order of service would be preaching, extempore prayer and congregational singing. The sole focus of attention would be the three Persons of the Trinity. There would have been no veneration of Saints or of the Mother of God. There would have been no religious orders. The congregation would have regarded themselves as spiritual equals, saved Christians, chosen ('elect') by the free grace of God and not for any virtues they themselves might possess or works they might have preformed, either of charity or of devotion.

These are all characteristics of Calvinism.

Samuel Charters in his account mentions two churches frequented by Johnson. One was the Mount Olivet Baptist Church in Marlin. Calvin was not a Baptist. Where the Baptists would argue that only adults knowing what they were doing should be baptised, Calvin argued in favour of baptising the children of church members in good standing. Nonetheless the Baptist tradition in the US derived for the most part from the English Baptist tradition, which had adopted a broadly Calvinist theological model.

He also attended the Church of God in Christ. This is now the largest of the black Pentecostalist churches, as well as, I think, the first. It separated from the Baptists in 1897. It departed further from traditional Calvinism in adopting a broadly Wesleyan 'Arminian' theory of grace. In contrast to the traditional Calvinist view that grace was offered only to those predestined by God to be saved, that it was irresistible and that once gained it could not be lost, the Arminians argued that grace was offered to all humanity, it could be resisted and it could be lost. Nonetheless I would still argue that the Church of God in Christ was an evolution of the North American Calvinist tradition.

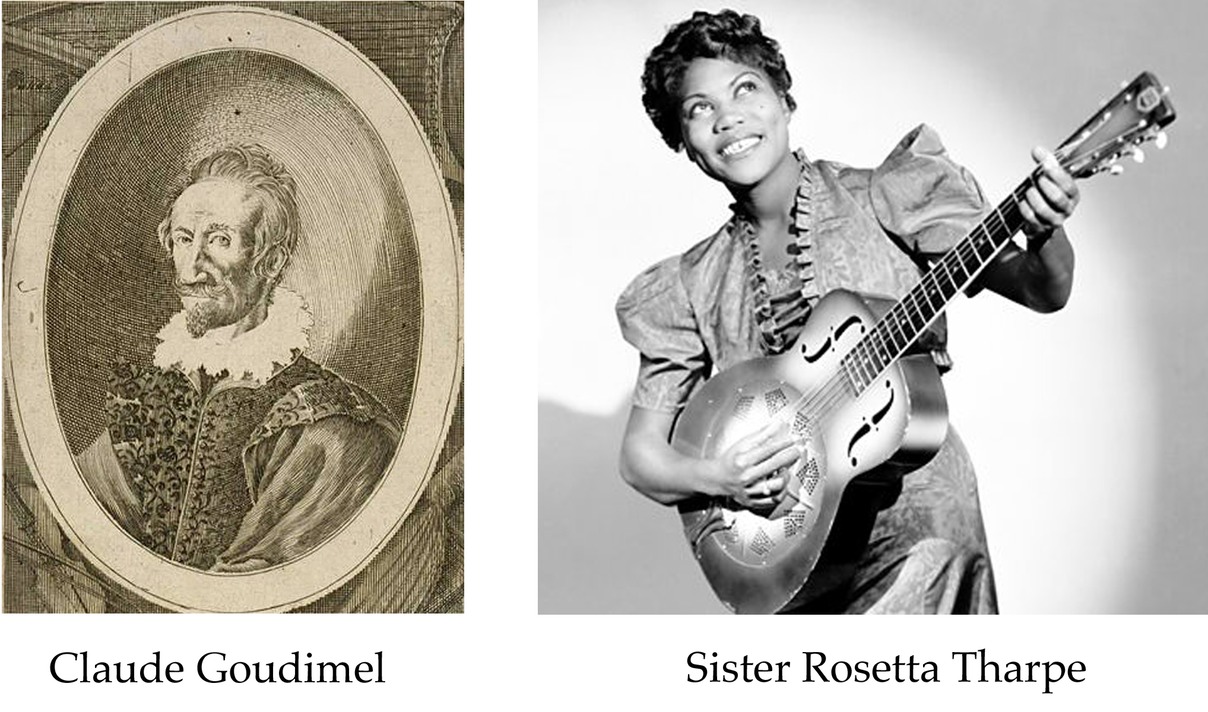

Having learned that the great Gospel singer, one of the pioneers of Rock'n'Roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, had also attended the Church of God in Christ I was unable to resist playing a piece by her - Ain't no grave gonna keep my body down, a much more high spirited version of a song later sung by Johnny Cash.

Distant as Sister Rosetta might appear to be from Calvin's Geneva, the emphasis on song is very much in line with Calvin's own teaching. In the Articles concerning the Organisation of the Church and of Worship at Geneva proposed by the Ministers at the Council, January 16, 1937, a document in which he is still feeling his way towards a more final statement as to how the church should be organised, he says:

'... there are the psalms which we desire to be sung in the Church, as we have it exemplified in the ancient Church and in the evidence of Paul himself, who says it is good to sing in the congregation with mouth and heart. We are unable to compute the profit and edification which will arise from this, except after having experimented. Certainly as things are, the prayers of the faithful are so cold, that we ought to be ashamed and dismayed. The psalms can incite us to lift up our hearts to God and move us to an ardour in invoking and exalting with praises the glory of his Name. Moreover it will be thus appreciated of what benefit and consolation the pope and those that belong to him have deprived the Church; for he has reduced the psalms, which ought to be true spiritual songs, to murmuring among themselves without any understanding.

'This manner of proceeding seemed specially good to us, that children, who beforehand have practised some modest church song, sing in a loud distinct voice, the people listening with all attention and following heartily what is sung with the mouth, till all become accustomed to sing communally ...'(2)

(2) Calvin: Theological Treatises, translated and edited by Rev. JKS Reid, Philadelphia, Westminster Press, 1954, pp.53-4

After Calvin was expelled from Geneva in 1538 he went to Strasbourg. According to one of his more recent biographers, T.H.L.Parker:

'The congregational singing that had been one of the four points in his policy for church reform in Geneva was introduced here also. The first of the metrical Psalters was published at Strasbourg in 1539 for the French church to use in its worship. A French-speaking refugee from the Low Countries wrote of how it affected him:

'"Everyone sings, men and women, and it is a lovely sight. Each has a music book in his hand ... For five or six days at the beginning as I looked on this little company of exiles, I wept, not for sadness but for joy to hear them all singing so heartily, and as they sang giving thanks to God that he had led them to a place where his name is glorified. No one can imagine what joy there is in singing the praises and wonders of the Lord in the mother tongue as they are sung here."'(3)

(3) T.H.L.Parker: John Calvin, Lion publishing, Berkhamsted, 1977 (1st ed 1975), p.83.

Parker continues (pp.103-4):

'Nothing is more characteristic of Reformation theology, and few parts of Reformation church activity have been so neglected as congregational singing. It was far from being a pleasant element introduced rather inconsistently into a service otherwise ruled by a sombre view of life. We have already seen that in 1537 one of the four foundations for the reform of the church was congregational singing. We have seen that in Strasbourg Calvin introduced singing into the French church. We have seen that it was demanded by the ordinances. We have seen in effect that Calvin placed singing at the heart of his theology of the church. The reason is not far to seek. To put it with the utmost simplicity: the church is the place where the gospel is preached; gospel is good news; good news makes people happy; happy people sing. But then, too, unhappy people may sing to cheer themselves up - "Art thou weary? music will charm thee." In the remarkable second half of the Epistle to the Reader (4) Calvin justifies his introduction of congregational singing.

(4) Calvin's preface to La Forme des Prieres et Chantz Ecclesiastiques issued in Geneva in 1542 soon after Calvin's return.

'He can easily justify it from early church practice, but this is not enough. He takes his stand on the influence of music in general which practically everyone feels: "Among other things which recreate man and give him pleasure [volupté!] music is either the first or at least one of the principal; and we should reckon it a gift of God intended for this use ... There is, as Plato has wisely considered, hardly anything in the world which can more turn or move men's ways in this or that direction. And in fact we experience that it has a great secret and almost incredible virtue to move hearts in one way or another."'

'No-one, we may note as a side-light on Calvin's character' Parker adds, 'could have written this who had not himself felt it.'(5)

(5) I illustrated this Calvinist Psalm singing with Claude Goudimel's arrangement of Psalm CXIV from the Genevan Psalter, Quand Israël hors d'Egypte sortit, and a more straightforwardly unadorned congregational rendering of Psalm LXI, Ne tens à ce que je crie, je te prie, sung by L'Oratoire du Louvre. This was still more of a concert version than I would have liked so I added Psalm LI, After Thy loving kindness, Lord, from the Scottish metrical psalter sung to the tune 'St Kilda' by the congregation of the Dowanvale Free Church.