A STABLE SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT?

So the Catholic 'resurgence' took two apparently contradictory forms. On the one hand they were advancing in positions of power and responsibility within Northern Ireland. On the other hand they were successfully defying a professional army that boasted (justifiably or not, that is another matter) of being among the most capable military forces in the world. One could see in this a division of class - middle class 'careerism', working class militancy. And one could see it reflected in the two main political parties - middle class SDLP, more working class Sinn Fein. But it is more accurate and useful to see it as two sides of single movement, a single resurgence.

It may have been the genius of John Hume that, despite being the leader of the SDLP, whose political representatives for the most part genuinely hated the IRA, he knew that the two sides of the resurgence were complementary, not contradictory. But he was faced with a problem. Left to its own devices the Northern Ireland problem risked finding a resolution that would certainly suit the 'careerist' side of the equation but would not solve the problem posed by the military side.

I must stress that I am not using the word 'careerist' in a derogatory sense. It was a merit of direct rule that career paths were opening for Catholics which had previously been closed. And this raised the question as to whether or not there was any need for a devolved legislature in Northern Ireland. A poll conducted in 1978 (the 'Northern Ireland attitude survey' by E.P.Moxon Browne and B.Boyle) found that 96.6% of Protestants and 92.2% of Catholics felt that 'Northern Ireland should have the same laws as the rest of the United Kingdom.' A series of National Opinion Poll surveys conducted between 1974 and 1982 had posed the question if 'integration' - direct rule from Westminster as a stable and permanent constitutional settlement - was an acceptable option. Large majorities of Protestants, fluctuating between 78% (1974) and 91% (1981) found it acceptable. That might seem unsurprising given that this was obviously the most 'Unionist' option, but we should bear in mind that it would have meant renouncing for good all the power and patronage that went with their most favoured option, majority rule devolution.

The figure among Catholics fluctuated between the lowest at 35% (1981) to the highest, 55% (1976). The figure in 1982 was 45%. Although of course much lower than the Protestant percentages, these figures are still remarkable given that this was the most 'Unionist' option and that all sections of the Catholic political establishment regarded it with the deepest hostility. Had equivalent percentages among the Protestant population regarded a united Ireland as an acceptable option the figures would have been recognised as significant.

What would have been necessary to bring it about? When Stormont was suspended, Northern Ireland was in the middle of a radical reorganisation of local government. According to an obituary for Sir Patrick Macrory, the architect of this reorganisation:

"Under the report, urban district, rural district and county councils were all abolished, their responsibilities for health care, education and planning transferred to Stormont and their remaining powers over things like dustbins and burial of the dead vested in 26 district councils. The removal of Stormont, never envisaged under the report, produced the famous Macrory Gap, eventually filled with largely nominated quangos to handle those important local government functions administered by councils in the rest of the UK." (3)

(3) The Independent, 13th May 1993

In the early 1980s, the Unionist Party under the leadership of James Molyneaux, argued for the re-establishment of Stormont, without legislative powers, as a top tier of local government that would fill the 'Macrory gap'. To satisfy the natural devolutionist desires of almost all professional politicians in Northern Ireland the policy was called 'administrative devolution', but it would have provided Northern Ireland with a perfectly adequate and democratic system of government. Arrangements could have been made for a division of responsibilities among the different parties, Catholic and Protestant and, given the engagement of all parties, including Sinn Fein, in the still available lower level of local government it would have been difficult to refuse engagement in the exercise of the more substantial powers (over education, health and planning) that would have been available in the upper tier. Which could easily have evolved into a legislature at some future date if that was thought to be desirable.

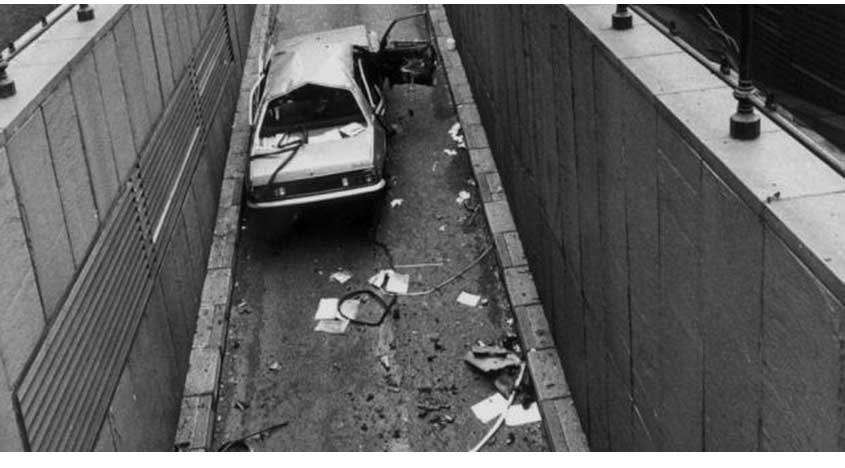

Interestingly, such a closing of the Macrory gap had been envisaged in the Conservative Party's 1979 manifesto which read: 'In the absence of devolved government, we will seek to establish one or more elected regional councils with a wide range of powers over local services.' It was widely believed that this apparently modest suggestion had been included on the initiative of Airey Neave, the Tory shadow secretary of state for Northern Ireland and a close friend and associate of Margaret Thatcher's. He had been killed by a bomb fixed under his car only a couple of days after the vote of no-confidence that brought down the Labour government and brought Margaret Thatcher into power. His Northern Ireland policy was almost immediately abandoned. When, in 1982, James Prior, as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, established yet another powerless Northern Ireland assembly as part of a process he called 'rolling devolution' the possibility of it becoming an upper tier of local government was deliberately excluded. The devolution to be rolled out could only be legislative devolution, granted when suitable agreement could be found (it never was) department by department.

The Airey Neave car bombing