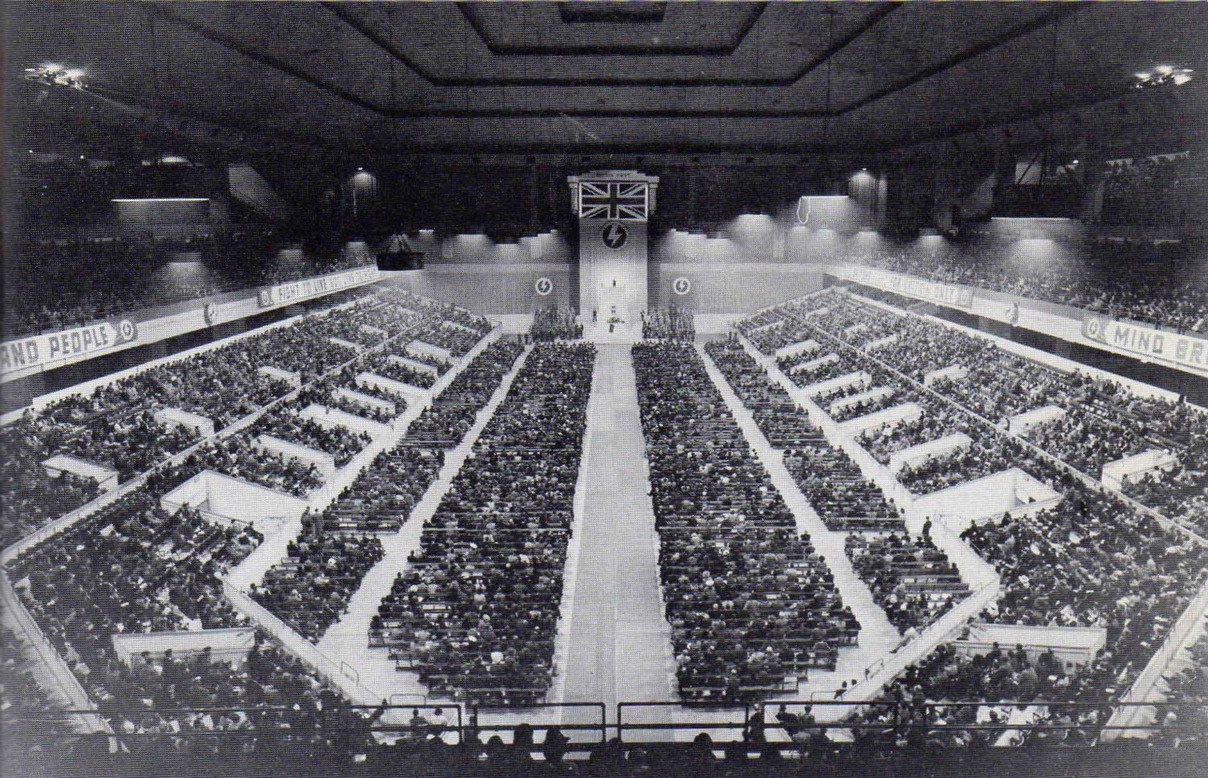

Mosley's anti-war rally in Earl's Court, 1939

PEACE WITH GERMANY

Britain, however, Mosley argued, could not win a war against Germany with its own resources. It could only win by mobilising America and Russia on its side. That could only mean American and Russian hegemony and the end of the Empire.

Robert Skidelsky, in his biography of Mosley (8) sums up his position as follows:

'Mosley's quest for peace and his National Socialism alike propelled him towards Anglo-German agreement, just as Churchill's refusal to contemplate such an agreement sprang from his lack of commitment to peace and from his hostility to Continental "tyrants". Churchill has recorded how he was "obsessed by the impression of the terrific Germany I had seen and felt in action during the years of 1914 to 1918 suddenly becoming again possessed of martial power ..." Mosley was obsessed with the gruesome slaughter of those years. To Churchill the First World War had been a successful if costly operation to preserve the traditional balance of power. For Mosley it finally discredited the whole idea of the balance of power. For Churchill nothing had changed. Britain must continue to "oppose the strongest, most dominating power on the Continent ..." For Mosley one purpose had replaced all the others: to remove the causes of war.

'But it is equally true that Churchill and Mosley were on different sides of the ideological divide in the 1930s. In Churchill's view Philip II, Louis XIV, Napoleon, Wilhelm II, Hitler were all tyrants endangering the liberties of others through their insatiable ambitions and who therefore needed to be "struck down". This was the main English tradition, the ideological basis of balance of power as England has always seen it. Democratic socialism, Liberal capitalism and League [of Nations - PB] idealism fitted into this tradition easily enough since all three were offshoots of the English ideology. Once Mosley had lost his belief that England's "free institutions" were the last word in civilisation, his commitment to this particular version of England's historic mission, already severely jolted by the First World War, disappeared altogether.' (pp.433-4).

(8) Robert Skidelsky: Oswald Mosley, Macmillan, 1975.

At the last moment before the war broke out Mosley had to dissuade Williamson from a quixotic project of going to Germany to speak to Hitler as one war veteran to another. Williamson naturally felt sympathetic to Rudolf Hess who had tried to do the same thing in reverse. The last novel in the Chronicle - The Gale of the world - features an old First World War fighter pilot ace, 'Buster' Cloudesley who develops a scheme for rescuing Hess from Spandau using glider planes. He has fond memories of chivalrous treatment at the hands of his wartime opponent, Hermann Göring:

'Herman Göring shot down Manfred Cloudesley over Mossy Face wood at Havrincourt in 1918. He saw that his enemy, who had killed nine of his Richthofen Staffel pilots, had the best surgeons and treatment in hospital. This morning Göring committed suicide. Better to have died on the cross, old Knight of the Ordre pour le Mérite.' (p.98)

Maddison's sense of outrage at the progress of the Nüremberg trial runs through the novel.

The title 'Gale of the World', incidentally, is a quotation from the Serb General Mihailovic, executed in 1946 on the order of Marshal Tito - 'shot in front of one of his daughters—a Communist; the father a Fascist, grey-bearded, manacle’d. I and all my works were caught in the gale of the world. The hail of bullets cutting bone and flesh. O fortunatus tu, mon general! If only I had died of my wounds on the Somme. Morbid thoughts no good. Breathe in slowly; as slowly respire; twenty times. "Be still, and know that I am God."' (Williamson). Prior to the German assault on the USSR, Mihailovic was the only person leading a military resistance in occupied Europe. When I was living in France I became friends with a distinguished former associate of De Gaulle's who told me De Gaulle had sent him on a private mission to Yugoslavia to inform Tito that so long as he (De Gaulle) had any power, Tito would not be allowed to set foot in France because of what he had done to Mihailovic.