WILLIAMSON AND THE WAR

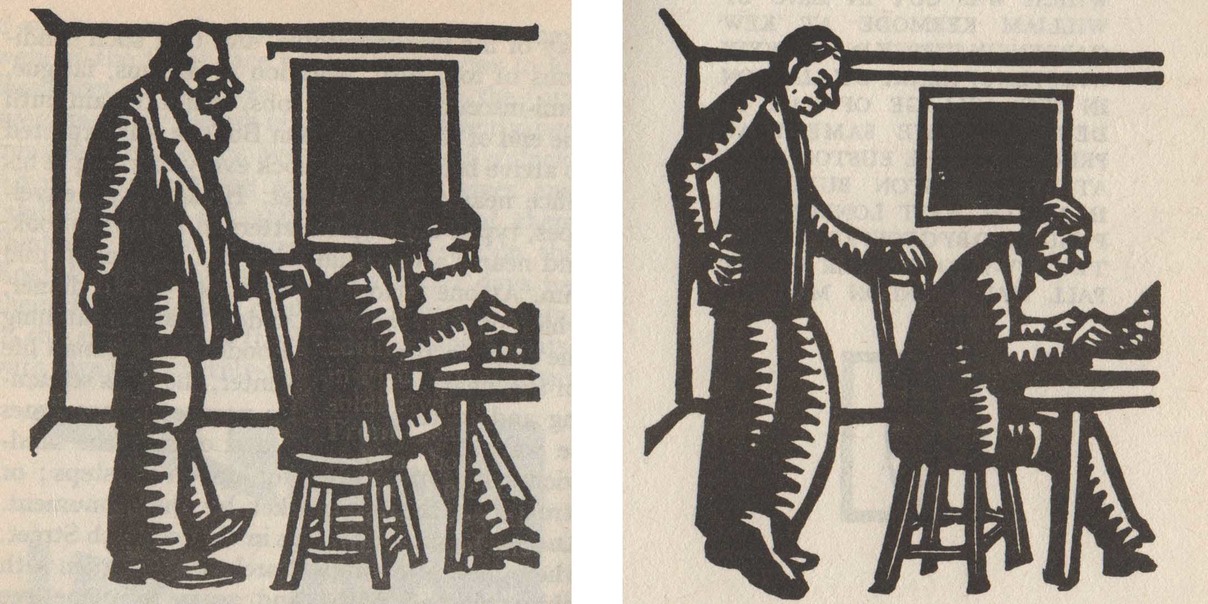

William Kermode: illustrations to Henry Williamson: The Patriot's Progress, first published, Geoffrey Bles, 1930.

Williamson's sympathy for Fascism in general and for Hitler in particular has its roots in his experience of the war and most particularly his presence at the famous 'truce' of Christmas 1914.

He describes the truce at some quite ecstatic length in A Fox under my cloak, fifth volume of the Chronicle. But he also evokes it in The Pathway, last of the four-volume sequence The Flax of Dream. This was his first major writing project after the war. It concerns Phillip Maddison's cousin, Willie, also based on Williamson himself but perhaps in a more fanciful and romantic form. The first two volumes concern his boyhood (The Beautiful Years) and adolescence (Dandelion Days). The last two volumes (The Dream of Fair Women and The Pathway) his adulthood and early death. The story of Dandelion Days, published in 1922, finishes in 1914. The Dream of Fair Women, published in 1924, begins in 1919. As Anne Williamson comments: 'HW avoids any direct portrayal of the war itself in this early work: he was still too close to this shocking era to be able to write about it – that was to come later.' (4)

(4) In her account of The Dream of Fair Women, accessible at https://www.henrywilliamson.co.uk/bibliography/a-lifes-work/the-dream-of-fair-women

Although with nothing like the depth of the five volumes given to the war in the Chronicle, it came quite soon, in two books - The Wet Flanders Plain, an account of a tour round the battle sites in 1927, and A Patriot's Progress, published in 1930. The progress achieved by the patriot is well shown in the illustrations by William Kermode. They begin with the patriot (an English everyman figure - 'John Bullock') in civilian life sitting at a desk in front of a typewriter with an old man standing behind him keeping an eye on what he is doing. They end with John Bullock as an older man sitting at a desk in front of a typewriter with a younger man standing behind him, keeping an eye on what he is doing. Bullock is now missing a leg. He has learned nothing from the dreadful experience he has been through. The book, a very powerful account with no hint of heroism in it, was serialised in Oswald Mosley's paper Action, in 1939.

The last volume of The Flax of Dream - 'The Pathway' - was published in 1928. Tarka the Otter, his first and perhaps his only taste of major success, was published in 1927. Anne Williamson makes the interesting suggestion that Tarka, full of violence as it is, 'can - and perhaps should - be read as an allegory of the First World War.' (5)

(5) In search of truth.

In The Pathway Willie Maddison emerges as a figure vaguely reminiscent of Dostoyevsky's Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. Like Myshkin he disturbs the settled life and ideas of a minor gentry family both because he has lived through something they cannot imagine and because he is possessed by a semi-religious idea which he sees as the necessary antidote to the ideas that created the war. In the course of a conversation in the novel, he describes the truce:

'"We were in trenches under Messines Hill, and had a truce with the Saxon regiment opposite. It started on Christmas Eve, when they were singing carols, and cheering 'Hoch der Kaiser!', and we cheered back for the king. Then they lifted a Christmas tree, lit with candles, on their parapet, and shouted for us to come over. We feared a trap; but at last one of us climbed out into no-man's land -"

'"That was you, I expect."

'"Well, yes, I did go. A German approached me. It was bright moonlight and the ground was frozen hard. We approached each other with trembling smiles, and hands fumbling in tunic pockets for gifts for each other. He could speak English. 'I saw you coming,' he said, 'and I've told my comrades not to fire, whatever happens. They appear to be afraid of a trap.' I was so moved that I could hardly speak. We shook hands over our barbed wire fence - in those days our barbed wire was a simple fence of five strands. He gave me cigars, and I gave him a tin of bully beef and some chocolate. After a while other men came out, and we stamped about and swung our arms to keep warm, smoking each other's Christmas tobacco ...

"The trenches were about a hundred and fifty yards apart where we were, and we stood about all Christmas Day in the flat turnip field, in which dead cows were lying - most of them riddled with bullets fired by young soldiers - including myself - wanting something to fire at, from both sides during the preceding days and weeks. The ground was bone-hard but we managed to bury the dead who had been lying out in no-man's land since the October fighting. We marked the shallow graves with crosses made of the wood of ration boxes. I talked with my German friend and asked him what the words 'Fur Vaterland und Freiheit' which were written in indelible pencil on their crosses meant. He said 'For Fatherland and Freedom.'

"This staggered me, for I had not thought for myself before; I believed, as nearly all English newspapers, priests, and politicians had declared, that it was a righteous war, to save civilisation; and that the Germans were all brutes, who raped women and bayoneted babies and old men, and had to be rooted out of Europe like a cancerous growth before the world could be safe. I was very young, you see, not then eighteen. My German friend said Germany could never be beaten; and I said, Oh no, England can never be beaten. He said Germany could not be beaten, because his country was fighting for the Right. I said, but we are fighting for the Right! How can you be fighting for the Right, also? We smiled at each other. He put his hand in his pocket and pulled out another cigar. 'Please smoke it, English comrade.'" (The Pathway, 1969 edition, p.226).

Earlier in The Pathway, in a conversation with Mary Ogilvie, a young woman who has befriended him, and her mother, Mrs Ogilvie, matriarch of the family, Willie protests against the way German was treated in the post-war settlement:

'"You know, William Blake, the poet who died about a hundred years ago! He was supposed to be mad, of course - the English always deprecate, or even destroy, their best minds. Blake wrote that lovely poem which was sung in so many schools during the war - Jerusalem:

'"I shall not cease from mental fight

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England's green and pleasant land

'"which various head masters and mistresses thought was a perfect expression of England's war aims for the annihilation of the German people. What stupidity, what blasphemy! The 'dark satanic mills' of Blake's earlier verse referred to the industrial system, which began the ruin of England: and which the financial power went to war to defend against continental industrial systems, first Napoleon, and then Germany! Poor Blake, a long watch he has been keeping! The lies that were told in the war, and are still being told, about the Germans! The humiliation of their Rhineland being occupied by the conquerors who knock off the hats of civilians who forget to raise their hats to French and Belgian officers! The agents provocateurs who arrange clashes between the rival political parties of resurgence in order to proclaim martial law! I have just been walking through Germany" he went on, in a rapid nervous voice, amidst complete silence, "and I know a little about it. It is terrible to see how that proud and truthful nation is brought low. The poor little starving children - why the starvation blockade was maintained until that revengeful treaty was signed at Versailles, eight months after the fighting ceased. Their bread was half sawdust. Scores of thousands of babies have died because of starvation."

'"It is retribution," exclaimed Mrs Ogilvie. Their defeat was the judgment of God! How can anyone think otherwise?" Her face was pale, her voice trembled.

'Maddison hesitated. He too was pale. He took a deep breath. "Good-bye," he said. "Thank you for welcoming me to your fireside," he added, while standing before her uncertainly, and holding out his hands to the flames. "I feel rather deeply about the war," he said, in a low, trembling voice.

'"You are not the only one," said Mrs Ogilvie.

'"Because, you know, it will happen again if all people do not examine themselves and see the cause of war in their own understanding of their neighbours. We are all war-makers, unless we know and watch ourselves."

'"I would rather not discuss it, if you do not mind," replied Mrs Ogilvie, putting down her needlework.'

Mrs Ogilvie had lost three sons in the war.