APPENDIX

(Articles written for the Radio Ulster series Your place and mine, published on the YPAM website, 2014)

(1) LIFE IN THE YARD

I had an interview at the age of twelve in 1944. In 1946 I started in the Belfast shipyard at the age of 14. I did 2 years as an office boy in the Thompson Works in a time office run by Billy Eason, a look-alike Clark Gable figure. He had an enormous sense of humour and was very kind to me and let me carry out some of his duties like giving the boards out through the pigeon-hole to the men and even making up the wages.

Thompson Works wasn't far from Deep Water Wharf where some of us swam in winter to harden up. And it worked. Coming out of the water, on which sleet was falling, most of us didn't have a towel but just put our clothes on over our wet bodies and we felt warmer than when we went into the water.

At that time the aircraft carrier Eagle was at Deep Water Wharf and of course there was always the solitary diver who soared into the water from the flight deck, maybe from near a 100 feet up. A crowd would gather to watch the event. The diver was a real showman - doing exercises on the deck for about five minutes before taking the plunge into the freezing water in a perfect arc. Nearby was the illegal pitch-and-Toss school where some of the men gambled at lunch time. They never looked up once at the diver but instead preferred to watch the coins on two boards being tossed into the air.

Launch of HMS Eagle, 1946

Others went round the crown and anchors boards to lose or gain a half-a-crown on board the ships tied up in Musgrave Channel. Then there were the card schools. A lot could be squeezed into forty minutes of a lunch time.

The Yard had a bus service. Two buses still camouflaged in khaki from WW2, the windows painted over with a bicycle-lamp bulb for internal lighting, even the headlamps were still hooded, showing only a slit. Two captured German ships were tied up in Musgrave Channel. And not far away there was about six flying boats floating, now out of service from the War. As fourteen-year-olds we would get a raft and row out to one of the German ships and take command shouting things like: `Yah yah, mein capitan, full steam ahead!' On one such journey our raft was swept away by a strong current until we were in the path of one of Kelly's coal boats chugging up Belfast Lough. A tugboat rescued us and the captain gave each of us a kick up the backside, which seemed to be normal in those days. Better than being handed over to the harbour police I suppose. The word `teenager' hadn't been invented them.

At 16 I entered the Joiner's Shop to serve my apprenticeship as a Joiner. Many of the woodworkers had been in the First World War and in 1948 men were still being de mobbed from the Second World War. So I learnt plenty about about world wars. I worked at Joe Beattie's bench. He had been captured while wounded on Crete during WW2. He was amazingly tolerant when I made mistakes in the making of something like a chest of drawers for example, though he had to take the responsibility for my mistakes. His maxim was: `The man who doesn't make a mistake hasn't made anything.'

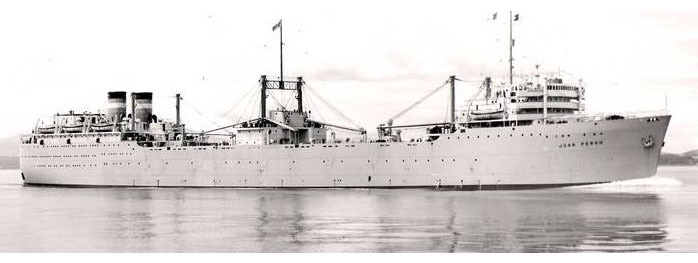

After a year in the Joiner's Shop we did a year on the ships. My father, a joiner, was on the Juan Peron whaling ship during the terrible accident when 9 men died as one of the gangways broke. He always had to be first off the ship but on that fatal evening he had forgotten his lunch box and went back to a cabin to get it. When he came back to the deck the accident had occurred. I sometimes met up with him and on that evening I went round to the Juan Peron and saw the horrifying scene of twisted bodies on the jetty. The memory was so horrifying that over the years I forgot about it and it was only a couple of years ago that I enquired about the date when it happened. I knew most of the dead men and the injured. Their faces still come back to me as if in a dream.

The gangway accident happened on the 31st of January, 1951. The death roll was eventually 18 dead - with two dying in hospital - and 59 injured. The Juan Peron was to be the biggest whaling factory ship in the world. At that stage of construction is was completely red-leaded and moored in the Musgrave Channel. It was a huge ship and its hull was very high out of the water which required two gangways: One led to a steel platform welded to the side of the ship. Another one ran parallel to the side of the ship to the cutting deck which was 50 feet above the jetty. Both gangways were made of timber. It was the parallel gangway that broke. Superstition still reigned then. Even the local media was writing about the gangway breaking at the thirteenth step.

The Juan Perón

But before that when I was an office boy in Billy Eason's time office in the Thompson Works a dreadful accident happened on the 11th of September, 1947. There was an explosion in the engine room of the Reina Del Pacifico, a former troop ship which was being converted back to its original role as a passenger ship to Cuba and Latin America. Twenty-eight men died and 23 were injured. The ship had been on shake-down trials and speed trials along the measured mile off the Clyde. All four engines had been put through their paces and seemed all right. The ship began to sail back to its berth in the Musgrave Channel when the engine room blew up without warning about seven miles off Copeland Island.

I heard the news on the radio on the evening of the 11th of September. Next morning I was giving out the boards in the time office (a board was made of wood, about three inches long by two inches wide with two ears between which a person's number was stamped. The ears were for picking it out of the wooden tray) when a fitter who had been on the ship entered and began talking in an agitated manner to Billy Eason. He had helped the doctor to administer morphine tablets to the injured. I remember he was almost out out of his mind in describing the horrors. He seized me and demonstrated how he had pushed the morphine tablets into the mouths of the injured men. Then he was bandaging Billy Eason's chest with imaginary bandages. To my embarrassment I burst out laughing.

Later the Reina Del Pacifico was towed up the Lough to Victoria Wharf. I couldn't wait to get round to see it. I imagined half the huge ship gone but there was no sign of damage on the outside, except for a patch of oily soot on the top of one of the yellow funnels. A huge crowd had gathered - men had just downed tools. Journalists were everywhere. The roof of a nearby workshop was crowded with sightseers. The harbour police couldn't get them off the asbestos roof and kept telling them it was dangerous.

Then the bodies, wrapped in white sheets began to be carried down the gangway on stretchers. One photographer gathered a few of us office boys together in order to take a photo. One boy began to slick his hair back with spittle and generally we were all smiling into the camera. The photographer kept telling us to put on a sad face but we couldn't. He gave up in disgust. We were fourteen and fifteen years old and the world of the adults was not quite real to us yet.

A few weeks later some of us sneaked aboard the disaster ship to look down into the vast engine room. It was a mess of tangled steel stairways and pipes with a smell of burnt oil. I wondered how anyone managed to survive that hell.

The Reina del Pacifico leaving the builders yard in Belfast in 1932

Besides these serious accidents the first-aid post were always very busy in the shipyard. Every ship I worked on had a death or two and many injuries. I was myself injured a few times but not seriously. With the macho atmosphere in the Yard you made light of having your head stitched after a heavy spanner fell on you from a height. (no hard hats then) Yet the older men near retirement were of the opinion that we teenagers would never match his generation that built ships like the Titanic. On top of that the war veterans from both world wars made us out to be milk sops if we complained about the cold or accidentally banging our fingernails black with a hammer.

In 1948 the Reina Del Pacifico was repaired and went back to its pre-war run between Liverpool and Valpariso. I watched it being towed out into Belfast Lough glistening white with two yellow funnels. It sure was the queen of the pacific as its Spanish name implied, and I longed to be onboard to visit exotic places it would visit.

In 1957 it went aground off Bermuda. A few months later it lost a propeller off Havana. A few years later the ship was scrapped in a shipyard in Monmouthshire. A ship was like a human being to most of we shipyard workers, always female and given the same respect we were supposed to give to our mothers. The Reina Del Pacifico, built in 1931, had survived WW2 but couldn't survive when passengers began taking to air travel. Most former shipyardmen must be happy at the advent of vessels once again sailing the oceans as cruise ships but is it the same as the old romantic days of the mighty passenger liner.

My uncle and cousins also worked in the Yard. My father had served his woodworking apprenticeship in Workman Clarks from 1914 to 1921. It was a seven-year apprenticeship then. Workman Clarks shipyard was not far from Harland and Wolff's. It closed down maybe in the 1920s and is largely forgotten today.

One of the jobs my father did was working on what was called the dummy aircraft carrier. It was made entirely of timber and was made to fool the enemy during WW2. But German reconnaissance were constant flying over the Yard which was an indication that there would be bombing raids soon.

Harland Wolff then began to build planes in line with Short and Harland's which was an aircraft builder near the Yard across a stretch of water. My father was asked if he would like to became what was called a dilute fitter. He accepted and was trained in metal work at Belfast Technical College. Soon afterwards he was working on building Stirling bombers seven days a week in artificial light. If you dared to take a couple of days off the police were at your door asking when you would be returning to work. It was priority war work.

On the night of the German air raids this aircraft factory was hit. My father went to work the next morning. Fires were still burning. Going through High Street, Belfast, the heat from the fires was so intense his hair singed. Getting to the aircraft works all he could see was molten metal in the shell of a building. The men were then set to work clearing up. It was up and running again in three months.

I left the shipyard in 1954 and went to London. My father continued to work in the Yard until retirement in 1965. He was a shipyardman all his life except for the 7 years he spent in New York from 1923 - 1930.

In 2004 I had a book published called The Yard. It was a series of long-short stories. The main one was about the shipyard. Later I wrote a more intense work about the shipyard as a novel but I have been unable to get it published. I think with Northern Ireland mostly given over to service industries and with its industrial might closed down industrial matters are now ignored or not understood anymore. So many wonderful skilled trades are now lost.

The shipyard had them all. They did everything from building the raw carcass of ships to the finishing of them - terrazzo floor laying, upholstery, curtain-making, french polishing were as important skills as caulking, welding, engine-building, shipwrighting and a hundred other trades to do with metal and engineering.

Shipyard humour was something that had you laughing no matter how cold and miserable you might be with the wind coming up Belfast Lough on a winter's day and it refrigerating the bare steel hull of a ship.

In London I eventually began to write plays for the theatre and had a few successes. I am still writing away. Out of the 35, 000 personnel there there were those with tremendous ambitions. Some were training and working to be footballers, cricketers, novelists, learning foreign languages, radio operators in the merchant navy, to be preachers. casino operators, professional dancers, actors, wrestlers, boxers, athletes. Many succeeded. The shipyard did that for us. It was a cosmopolitan scene with all the ships of many nations coming in for repair and refurbishment.

We met so many different nationalities that the rest of Northern Ireland were unlikely to meet. I hope a fully-fledged shipyard will rise again some day on Queens Island. Don't let it be built over with expensive town houses looking over vacant sterile waters with the cranes Samson and Goliath being mere platforms for an expensive restaurant.

To finish: Does anyone remember the man with the shotgun whose job was to shoot pigeons and starlings? He had a hut around the Thompson Dry Dock. I remember him with a wheelbarrow load of dead birds going into dry dock pumping station to burn them in the furnace.